In case you’ve been hiding under a rock (or from any form of news, social media, or conversation with other folks) this week: the Pope is in town.

Or, rather, Pope Francis has spent the past week visiting the United States. His visit has been widely publicized and talked about. People are stirring and moving, have been stirred and moved, and will continue to stir and to be moved over Pope Francis’ words and calls to action for us. About economics and politics and war and — especially and — the environment. About these things and more, that affect — so deeply — our communities, our homes, and our land. These things that affect our earth and our relationship to it.

In his address to Congress, Pope Francis said:

“We need a conversation which includes everyone, since the environmental challenge we are undergoing, and its human roots, concern and affect us all.”

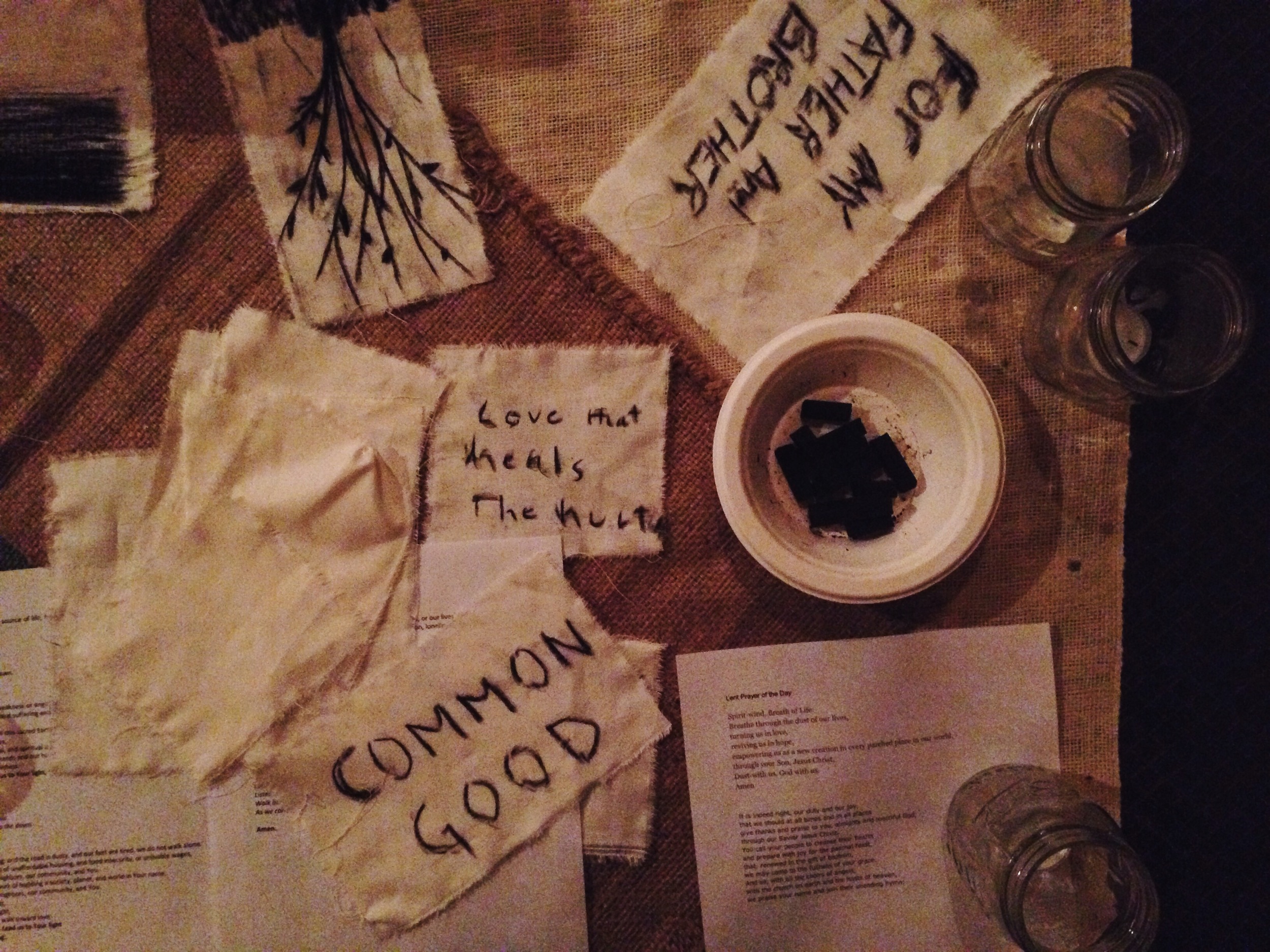

And I couldn’t help but think of the Pope’s words — many more than just these — that are connected to what’s been stirring in our own community. We are now in the midst of our Green Season: sharing our housing and land stories, reading the Pope’s encyclical on care for our common home before worship, immersing ourselves in this new liturgical season. We are diving into conversation about things that affect — so deeply — our communities, our homes, our land. Our earth. And our relationship to our earth.

And we all have one. A relationship to our earth. Pastor Melissa has been saying every Sunday — “If you live in Portland, you have a housing story.” And, in some ways, we can expand that statement to fully capture Pope Francis’ message about the environment:

“If you live here — on this land, on this earth, on this planet — you have a land story. And a land story is an earth story. And an earth story is, at its core, an environment story. And that affects us all.”

So what are these stories? When I first read Pope Francis’ words, I thought of my own land story, which is, by default, my family’s land story. And with that land story is a caretaking story.

My grandparents have lived on the same land since my mother was a small child, settling next to my great-grandparents’ home, the same place where my grandmother grew up. Each side of their home is surrounded by fields for miles: fields of corn, wheat, and soybeans. My great-grandparents farmed that land, and my mom would spend her summers throughout high school on the tractor, prepping the dirt and the earth for new life, or next to my grandfather on the combine, reaping and threshing and winnowing the crops.

I have memories of playing in grain bins, riding in my grandfather’s pick-up truck to visit the fields, waving at the neighbors — other farmers — as they kicked up gravel on their drives to the fields. While my grandparents don’t farm anymore, they are still deeply connected to their land. To the West of their house, my grandmother has the biggest and most bountiful flower garden you have ever seen. To the East, my grandfather spends hours each summer in the vegetable garden. He grows and cares — so carefully cares — for corn and squash and potatoes and a whole lot more.

My family has roots in this land — messy, muddy, dirt-under-the-fingernails, hundred-plus-year-old roots. They care for this land like they have cared for me, for each other, for all of our loved ones: with tenderness, persistence, and patience.

And this care for the land — this tenderness, persistence, and patience — is what God calls us into. God accompanies us in our care for our earth. In our care for our land, our homes, and our communities.

When Jesus begins speaking in today’s Gospel — our Father in heaven — the use of the word “Father” isn’t necessarily intended to be exclusive language, only geared toward the “traditional father figure” of the house, leaving out anyone who wasn’t male. Although, trust me, when I saw today’s Gospel text, I have to admit, I got a little internally feisty. I — raised by a single mother — was supposed to focus exclusively on this phrase that seemed so rooted in historical patriarchy?

“Our Father in heaven.”

“Our Father, who art in heaven.”

“Abba God in heaven.”

But, after spending some time with other biblical scholars, particularly John Dominic Crossen and his book The Greatest Prayer, I put some of that feistiness aside and learned more about how “Father” is actually a way to talk about God as a caretaker. According to Crossen, “Father” often referred not only to “Father and Mother,” but can be read as even more inclusive: the “householder,” or the one who cares for an entire home and entire family. So, maybe it's like my grandfather, who has been a caretaker for his land and his extended family. Or maybe it’s like my mother, who has been the head of my house, playing both Father and Mother. “Our Father” becomes the one who cares for and loves a home and its people: with tenderness, persistence, and patience.

That made my feminist-self feel a little bit better. Because praying “Our Father in heaven,” then, can be seen as a way to pray to God who is our caretaker; to pray to God who is the “head of house” for our entire world. Who cares for it, and for us, and our land: with tenderness, persistence, and patience.

And who calls us to do the same.

We are invited to be caretakers — for our own, immediate households, yes: for those who share our beds and dinner tables and four-walled structures. But we are also invited into an expansive definition of who is in our care, who is our neighbor, who is our family, who — and what — God calls us to care for. This care includes our surroundings: the plant and animal and insect life that breathes all around us, the food that nourishes us, and the land and Earth that provides for all of that.

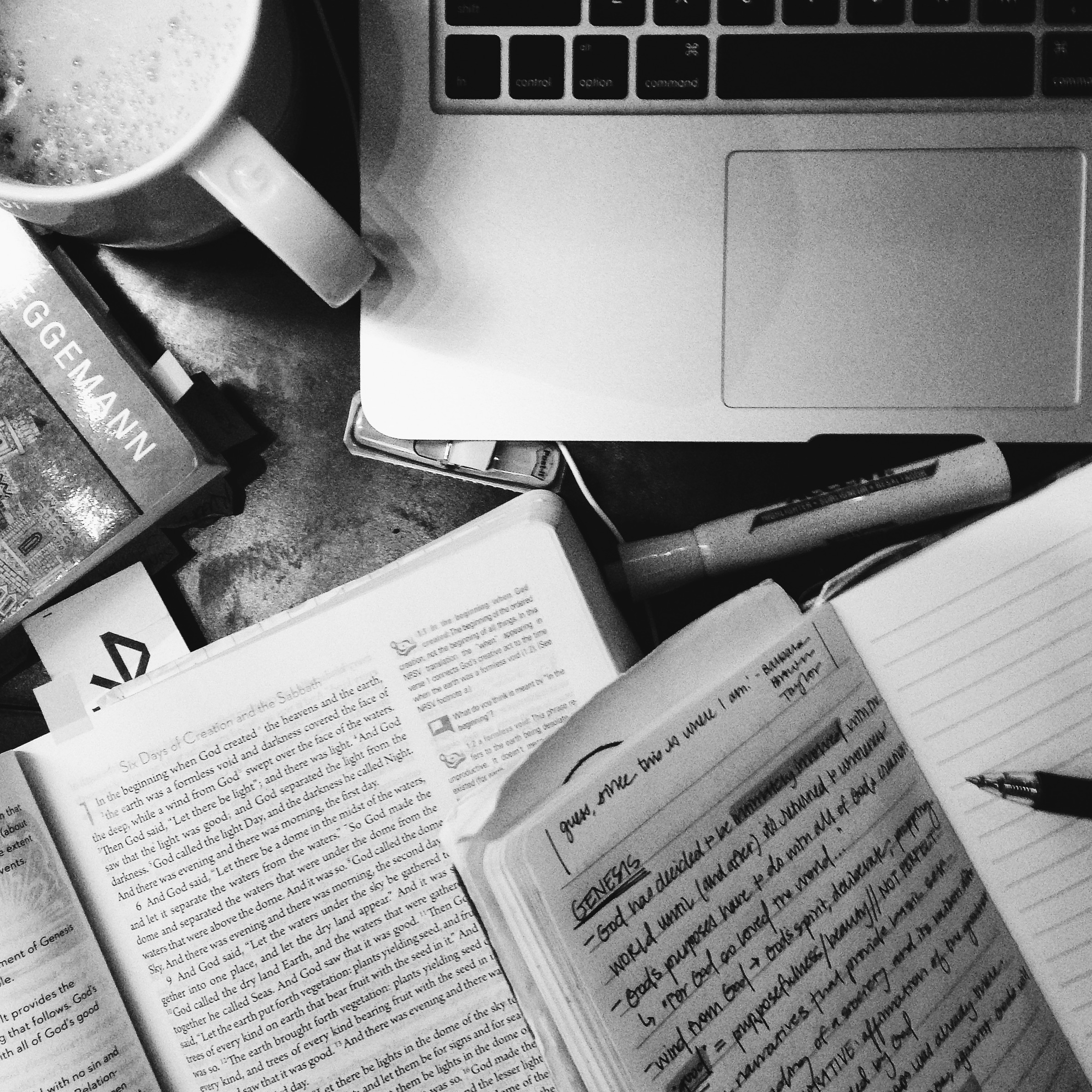

God invites us to care for who and what God has created and birthed from this universe: our earth, our land, our people. God formed us, shaped us, breathed life into us for this purpose. We read in Genesis:

“Then the Lord God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.”

The same reading makes note that there was no one to till the ground before this. God breathed life into that living being — and continues to breathe life into us — to be the caretakers and householders. To love and care for this land as God does.

But we cannot care for our earth in isolation. Jesus does not invite us to pray The Lord’s Prayer each day:

“My Father in heaven.”

“My Father, who art in heaven.”

“My Abba God in heaven.”

Even when we pray this prayer in solitude, standing in our darkened kitchens or lying in our warm beds or walking on the earth outside — when we pray for climate justice and housing justice and distributive justice for all on this earth — we are reminded that we are not called to act in solitude. Jesus calls us into our:

“Our Father in heaven.”

“Our Father, who art in heaven.”

“Abba God in heaven.”

Jesus calls us out of isolation and into community, called to come together to care for our earth: its shrubs and plants, ground and dust, all of its living beings. Each other.

Pope Francis said:

“We need a conversation which includes everyone, since the environmental challenge we are undergoing, and its human roots, concern and affect us all.”

We know this, though. We have known this. Our Leaven Community is rooted in this: opening up conversations and coming together to care for each other and our shared land. God empowers us to be caretakers and householders — filled with tenderness, persistence, and patience — together.

And so, together, we pray and continue these land conversations this season — which includes everyone, since everyone has a land, an earth, and an environment story. We pray, continue the conversation, and act — for justice for all and for our earth.